Consensus

Blockchain nodes use consensus engines to agree on the blockchain's state. This article covers the fundamentals of consensus in blockchain systems, how consensus interacts with the runtime in the Substrate framework, and the consensus engines available with the framework.

State machines and conflicts

A blockchain runtime is a state machine. It has some internal state, and state transition function that allows it to transition from its current state to a future state. In most runtimes there are states that have valid transitions to multiple future states, but a single transition must be selected.

Blockchains must agree on:

- Some initial state, called "genesis",

- A series of state transitions, each called a "block", and

- A final (current) state.

In order to agree on the resulting state after a transition, all operations within a blockchain's state transition function must be deterministic.

Conflict exclusion

In centralized systems, the central authority chooses among mutually exclusive alternatives by recording state transitions in the order it sees them, and choosing the first of the competing alternatives when a conflict arises. In decentralized systems, the nodes will see transactions in different orders, and thus they must use a more elaborate method to exclude transactions. As a further complication, blockchain networks strive to be fault tolerant, which means that they should continue to provide consistent data even if some participants are not following the rules.

Blockchains batch transactions into blocks and have some method to select which participant has the right to submit a block. For example, in a proof-of-work chain, the node that finds a valid proof of work first has the right to submit a block to the chain.

Substrate provides several block construction algorithms and also allows you to create your own:

- Aura (round robin)

- BABE (slot-based)

- Proof of Work

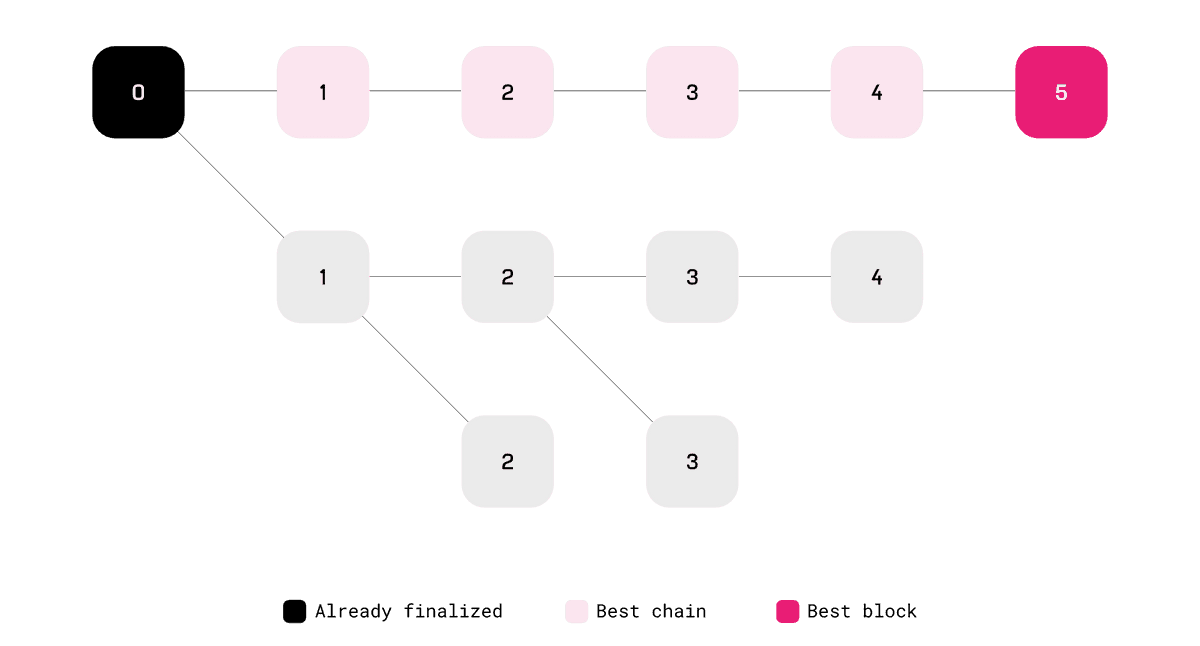

Fork choice rules

As a primitive, a block contains a header and a batch of extrinsics. The header must contain a reference to its parent block such that one can trace the chain to its genesis. Forks occur when two blocks reference the same parent. Forks must be resolved such that only one, canonical chain exists.

A fork choice rule is an algorithm that takes a blockchain and selects the "best" chain, and thus

the one that should be extended. Substrate exposes this concept through the

SelectChain Trait.

Substrate allows you to write a custom fork choice rule, or use one that comes out of the box. For example:

Longest chain rule

The longest chain rule simply says that the best chain is the longest chain. Substrate provides this

chain selection rule with the

LongestChain struct.

GRANDPA uses the longest chain rule for voting.

GHOST rule

The Greedy Heaviest Observed SubTree rule says that, starting at the genesis block, each fork is resolved by choosing the branch that has the most blocks built on it recursively.

Block production

Some nodes in a blockchain network are able to produce new blocks, a process known as authoring. Exactly which nodes may author blocks depends on which consensus engine you're using. In a centralized network, a single node might author all the blocks, whereas in a completely permissionless network, an algorithm must select the block author at each height.

Proof of Work

In proof-of-work systems like Bitcoin, any node may produce a block at any time, so long as it has solved a computationally-intensive problem. Solving the problem takes CPU time, and thus miners can only produce blocks in proportion with their computing resources. Substrate provides a proof-of-work block production engine.

Slots

Slot-based consensus algorithms must have a known set of validators who are permitted to produce blocks. Time is divided up into discrete slots, and during each slot only some of the validators may produce a block. The specifics of which validators can author blocks during each slot vary from engine to engine. Substrate provides Aura and Babe, both of which are slot-based block authoring engines.

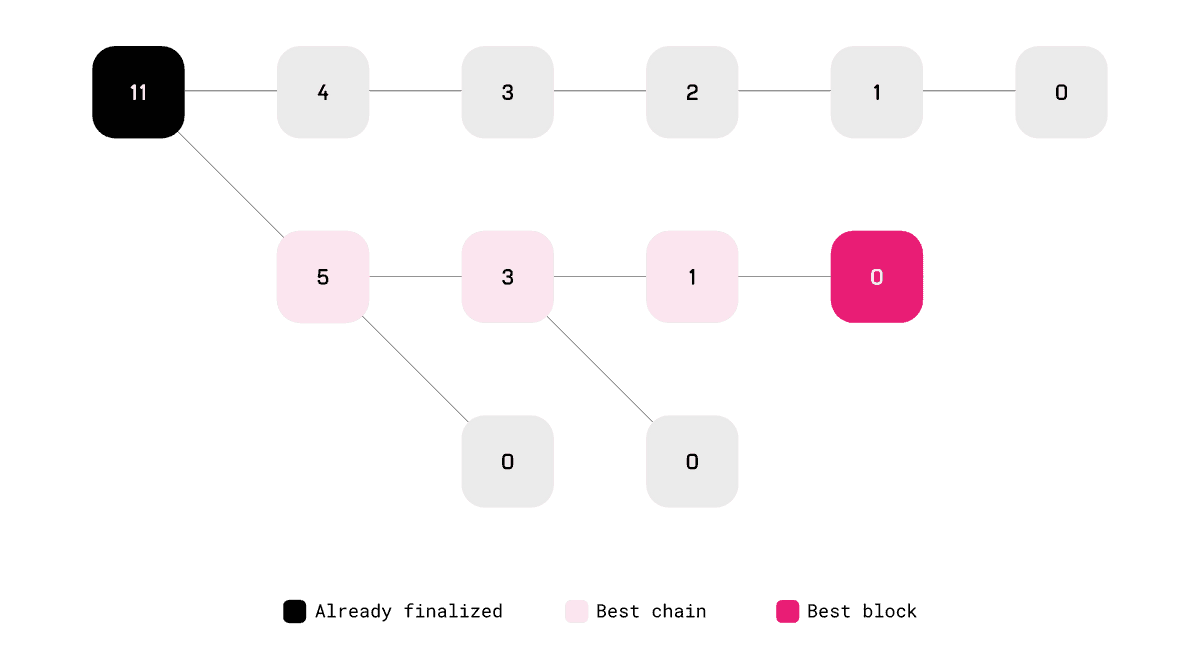

Finality

Users in any system want to know when their transactions are finalized, and blockchain is no different. In some traditional systems, finality happens when a receipt is handed over, or papers are signed.

Using the block authoring schemes and fork choice rules described so far, transactions are never entirely finalized. There is always a chance that a longer (or heavier) chain will come along and revert your transaction. However, the more blocks are built on top of a particular block, the less likely it is to ever be reverted. In this way, block authoring along with a proper fork choice rule provides probabilistic finality.

When deterministic finality is desired, a finality gadget can be added to the blockchain's logic. Members of a fixed authority set cast finality votes, and when enough votes have been cast for a certain block, the block is deemed final. In most systems, this threshold is 2/3. Blocks that have been finalized by such a gadget cannot be reverted without external coordination such as a hard fork.

Some consensus systems couple block production and finality, as in, finalization is part of the

block production process and a new block N+1 cannot be authored until block N is finalize.

Substrate, however, isolates the two processes and allows you to use any block production engine

on its own with probabilistic finality or couple it with a finality gadget to have determinsitic

finality.

In systems that use a finality gadget, the fork choice rule must be modified to consider the results of the finality game. For example, instead of taking the longest chain period, a node would take the longest chain that contains the most recently finalized block.

Consensus in Substrate

The Substrate framework ships with several consensus engines that provide block authoring, or finality. This article provides a brief overview of the offerings included with Substrate itself. Developers are always welcome to provide their own custom consensus algorithms.

Aura

Aura provides a slot-based block authoring mechanism. In Aura a known set of authorities take turns producing blocks.

BABE

BABE also provides slot-based block authoring with a known set of validators. In these ways it is similar to Aura. Unlike Aura, slot assignment is based on the evaluation of a Verifiable Random Function (VRF). Each validator is assigned a weight for an epoch. This epoch is broken up into slots and the validator evaluates its VRF at each slot. For each slot that the validator's VRF output is below its weight, it is allowed to author a block.

Because multiple validators may be able to produce a block during the same slot, forks are more common in BABE than they are in Aura, and are common even in good network conditions.

Substrate's implementation of BABE also has a fallback mechanism for when no authorities are chosen in a given slot. These "secondary" slot assignments allow BABE to achieve a constant block time.

Proof of Work

Proof-of-work block authoring is not slot-based and does not require a known authority set. In proof of work, anyone can produce a block at any time, so long as they can solve a computationally challenging problem (typically a hash preimage search). The difficulty of this problem can be tuned to provide a statistical target block time.

GRANDPA

GRANDPA provides block finalization. It has a known weighted authority set like BABE. However, GRANDPA does not author blocks; it just listens to gossip about blocks that have been produced by some authoring engine like the three discussed above. GRANDPA validators vote on chains, not blocks, i.e. they vote on a block that they consider "best" and their votes are applied transitively to all previous blocks. Once more than 2/3 of the GRANDPA authorities have voted for a particular block, it is considered final.

Coordination with the Runtime

The simplest static consensus algorithms work entirely outside of the runtime as we've described so far. However many consensus games are made much more powerful by adding features that require coordination with the runtime. Examples include adjustable difficulty in proof of work, authority rotation in proof of authority, and stake-based weighting in proof-of-stake networks.

To accommodate these consensus features, Substrate has the concept of a

DigestItem, a message

passed from the outer part of the node, where consensus lives, to the runtime, or vice versa.

Learn more

Because both BABE and GRANDPA will be used in the Polkadot network, Web3 Foundation provides research-level presentations of the algorithms.

All deterministic finality algorithms, including GRANDPA, require at least 2f + 1 non-faulty

nodes, where f is the number of faulty or malicious nodes. Learn more about where this threshold

comes from and why it is ideal in the seminal paper

Reaching Agreement in the Presence of Faults

or on Wikipedia: Byzantine Fault.

Not all consensus protocols define a single, canonical chain. Some protocols validate directed acyclic graphs (DAG) when two blocks with the same parent do not have conflicting state changes.